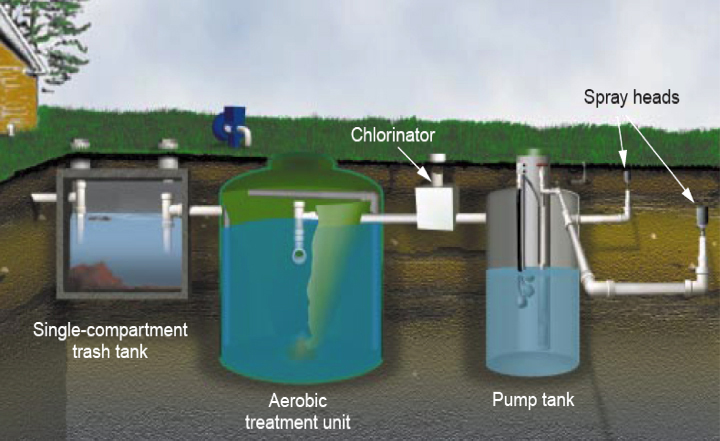

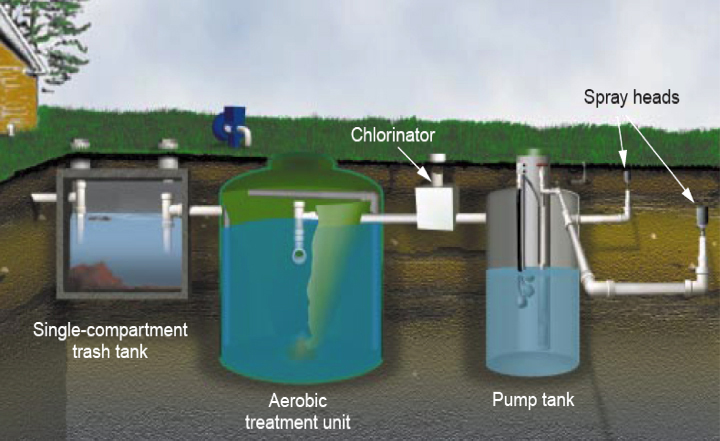

Aerobic Treatment Systems (ATS) collect residential grey water and wastewater leaving homes and discharging the treated effluent on lawns in residential settings (Figure 1). ATS installations are increasing in number throughout the U.S., according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) (USEPA, 2000). ATS are viewed as a beneficial water conservation method because they recycle treated wastewater for outdoor irrigation. Proper operation methods and maintenance requirements are included to provide ATS owners/operators information to properly care for on-site septic systems. Concerns associated with ATS are also discussed to alert users to potential contamination to surface water that may result from poorly maintained or improperly installed systems.

Figure 1. Aerobic Treatment System Treatment Diagram (left to right). (Source: ODEQ, 2011e)

ATS collect and treat wastewater leaving homes and recycle the treated wastewater for outdoor irrigation. Currently, ATS are being installed as a replacement for failing septic systems in the U.S. (USEPA, 2000) and in newly constructed residences. ATS is usually chosen only if soil and site characteristics are not suited for other simpler systems, such as septic fields. Homebuilders find the idea of offsetting outdoor irrigation costs as an attractive benefit of ATS compared to traditional septic systems. Homebuilders and developers may prefer the installation of ATS compared to septic systems because they use less yard space and allow homes spaced closer when building a residential development (OEDQ, ASTS). Another key benefit for ATS installation in Oklahoma is their suitability for poor quality clay or very sandy soils.

ATS have a high initial cost for installation; however, ATS costs decline through time (ODEQ, ASTS). In Oklahoma (2015), bids for new installation of a residential ATS were roughly $5,500 to $5,700, including a 2-year warranty and four routine inspections. A one-year service contract would cost $150 to $225. A one-time inspection of an ATU would cost $190. ATS should be serviced and maintained for two years by law after installation by a certified installer (ODEQ, 2012). The certified installer covers all costs associated with maintenance performed for the first two years after installation, or amounts agreed upon in a signed contract with the homeowner.

After an ATS has been installed and maintained by a certified installer for two years, the maintenance and operation requirements must be performed by the homeowner (ATS owner/operator) or by a renewed or newly contracted certified maintenance company. Ongoing costs covered by the homeowner (owner/operator) may include sludge removal. The fee for hiring a certified technician to collect the sludge from the pre-treatment tank along with the charge for proper disposal methods will be paid by the homeowner. The sludge removal process should occur at regular intervals and be determined by the loading rate and size capacity of each system (ATS).

ATS collect all water leaving a home in a pre-treatment/trash tank. Solids collect near the bottom of the tank (sludge) and the liquid is transported to the aerobic treatment unit/aeration tank (Figure 1). The aeration tank is designed to treat the wastewater through a process of nitrate reduction (ODEQ, 2012). Nitrogen reduction occurs in an aerobic system by microorganisms and bacteria present in the system. Nitrogen is oxidized in the aeration tank by the air that is bubbled into the tank, which causes nitrogen and ammonium to be oxidized into nitrate. Nitrate is then reduced to nitrogen gas during a period in which the aerators are turned off.

Chlorine should be added per manufacturer instructions regarding disinfection. The homeowner is also responsible for adding chlorine to the treatment tank daily, as well as the cost of the chlorine. Chlorine must be deposited in the treatment tank by the homeowner (owner/operator) to treat the waste with chlorination disinfection prior to disposal through subsurface drip or spray irrigation (ODEQ, 2012).

Once disinfection occurs, the treated wastewater is transported to the holding or pump tank where the water can then be used for outdoor irrigation purposes. Surface irrigation, the most common practice in Oklahoma, is a less expensive way of disposing of effluent, but subsurface drip is safer in terms of avoiding contact with potential contaminants. A drip tube irrigation piping system located at least 30 cm below the soil surface is the safest disposal method for treated wastewater (Franti et al. 2002).

A certified installer must be licensed before installing an ATS. A certified installer will perform proper maintenance requirements associated with ATS for two years after installation. Once the certified installer’s agreement expires (two years after installation), all duties performed by the certified installer initially are then transferred to the homeowner (owner/operator) as defined by the ATS regulatory standards in Oklahoma (ODEQ, 2012).

ATS maintenance duties include but are not limited to ensuring that “…sewage or effluent from the system is properly treated and does not surface, pool, flow across the ground or discharge to surface waters” (ODEQ, 2012). ATS may discharge treated effluent only when daily inputs are greater than 100 gallons or less than 1,500 gallons per day (ODEQ, 2012). ATS-treated wastewater may only be discharged between 1 a.m. and 6 a.m., with no exceptions (ODEQ, ASTS).

Water clarity may be measured by a secchi disk (an instrument used for measuring water clarity) and the bottom of the holding or pump tank must be visible at all times. If a homeowner chooses to discharge treated effluent through spray irrigation, “…a free chlorine residual of one-fifth of a milligram per liter (0.2 mg/l) must be maintained in the pump tank.” Fecal coliform bacteria should not exceed 200 cfu (colony forming units)/100 mL (ODEQ, 2012).

Pathogenic bacteria have the potential to contaminate creeks and streams during rainfall events. Reports of human illness are associated with swimming, drinking or ingesting contaminated water with E. coli and fecal coliform bacteria. “Fecal coliforms are bacteria that are associated with human or animal wastes.” The USEPA has set a Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG) for fecal coliforms at zero for drinking water. According to the USEPA “Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a type of fecal coliform bacteria… found in the intestines of animals and humans. …E. coli is a strong indication of recent sewage or animal contamination. …Sewage may contain many types of disease-causing organisms” (USEPA, 2013a).

ATS owners/operators do not need to obtain an Oklahoma Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (OPDES) permit prior to discharging treated effluent to the surface (ODEQ, 2011d). Specifications of ATS disposal are not specified (ODEQ, 2012). Dependent upon the size and location of the ATS, OKDEQ may consider requiring an OPDES permit prior to discharging treated effluent.

Standards for ATS include fecal coliform bacteria concentrations (ODEQ, 2012. Standards specify ATS should not exceed fecal coliform concentrations above 200 cfu/100 mL per sample; however, fecal coliform sampling and testing requirements are not required (ODEQ, 2012). Rules and regulations associated with ATS in Oklahoma do not include E. coli standards (ODEQ, 2012).

In a 2014 study of three typically installed ATS in Oklahoma, approximately 10,000 to 200,000 most probable number (MPN)/100 mL fecal coliform concentrations were quantified from ATS holding (pump) tanks. Approximately 1,000 to 100,000 MPN/100 mL E. coli concentrations were quantified from these same holding tanks (Stambaugh, 2014). Please note that cfu and MPN are interchangeable; MPN was the unit used in this study (Stambaugh, 2014) However, the USEPA states that systems are “…required to disinfect to ensure that all bacterial contamination is inactivated, such as E. coli” (USEPA, 2013a).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012. E. coli (Escherichia coli). General Information: Escherichia coli (E. coli). (January 2014).

Franti, J.M., Weaver, R.W., and McInnes, K.J. 2002. Surfacing of domestic wastewater applied to soil through drip tubing and reduction in numbers of Escherichia coli. Environmental Technology 23: 1027-1032

Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ). Aerobic Sewage Treatment System (ASTS). Operation and Maintenance Guide for Homeowners. (April 2014).

Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ). 2011d. Oklahoma DEQ Rules and Regulations/Legal Information. 252:606 Oklahoma Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (OPDES) Standards. (February 2014).

Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ) 2011e. Aerobic System Maintenance. (May 2015)

Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ). 2012. Oklahoma DEQ Rules and Regulations/Legal Information. 252:641 Individual and Small Public Onsite Sewage Treatment Systems. (January 2014).

Stambaugh, K. 2014. Bacterial assessment of applied treated effluent from wastewater systems. M.S. Thesis. Environmental Science. Oklahoma State University.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2000. Decentralized Systems Technology Fact Sheet: Aerobic Treatment. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Water. Washington, D.C. EPA 832-F-00-031. September 2000 Agency.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2013a. Water: Basic Information about Regulated Drinking Water Contaminants. Basic Information about E. coli 0157:H7 in Drinking Water. (January 2014).

Kasie D. Stambaugh

Graduate Student, Environmental Science

Tracy A. Boyer

Associate Professor, Agricultural Economics

Garey A. Fox

Professor and Buchanan Endowed Chair

Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering